The 2026 general election has ended, but the truth has not been sealed. It’s because after ballots are cast, what continues to circulate in society is not only the vote count, but also ambiguous information, half-truths, and distorted narratives. All of these continue to relentlessly test the resilience of democracy.

For Thai PBS Verify, an election is not the finish line; it is merely a turning point of its mission. The real battlefield is not in the polling booth, but on the screen.

Experience throughout the election period has made it clear that the most dangerous threats do not arise on debate stages, but in the online world, where no night is ever quiet. Every night is a “night of the howling dogs,” as “malinformation” can spread online at any time—without waiting for the final stretch, without waiting for the 24-hour blackout before election day. Every moment is an opportunity for information to be released without resistance.

“Malinformation”: a deceptive tactic that doesn’t fully lie, but intentionally misleads

Malinformation is not fake news in the sense of being completely fabricated. It involves real people, real events, and real statements—but they are placed in the wrong context and wrong timing, or framed in a misleading way. The danger of malinformation lies not in outright falsehood, but in deliberate ambiguity that twists meaning without directly lying. It appeals to emotion before reason, pushing audiences to make quick judgments without realizing it.

This is why malinformation is harder to verify than fake news. It does not exist in a world of “true” or “false,” but in a “gray zone” that demands greater care, patience, and responsibility from those who evaluate it.

Challenges of verifying political news

Political news during election periods is rarely a matter of right or wrong. More often, it involves damaging reputations through old information, selective storytelling, or narratives that carry audiences far beyond the facts.

In many cases, what is presented is “political opinion.” It should not be judged as true or false. In other cases, the information may be accurate in one context but misleading in another. “Snap judgments,” therefore, may become a distortion of the truth.

In this area, there are no shortcuts for news consumers. The only way is to read more deeply, take some time, and revisit sources more carefully than before. Political decisions should not be guided by incomplete information. The most dangerous form of misinformation is not outright falsehoods, but narratives that blend facts, opinions, emotions, and rhetoric together.

Rhetoric such as “selling out the country,” “gray capital,” or “overthrowing the institution” does not function as factual information. Instead, it appears in the form of narratives that are difficult to determine as entirely true or false. Audiences therefore must learn to distinguish what is information, what is opinion, and what is emotional manipulation. Even if such information aligns with our own beliefs, if it is distorted, it remains unfair information and leads to flawed decisions, a state of being misinformed that quietly undermines elections.

A new ‘fact-check’ label: when making an indefinite call is media’s responsibility

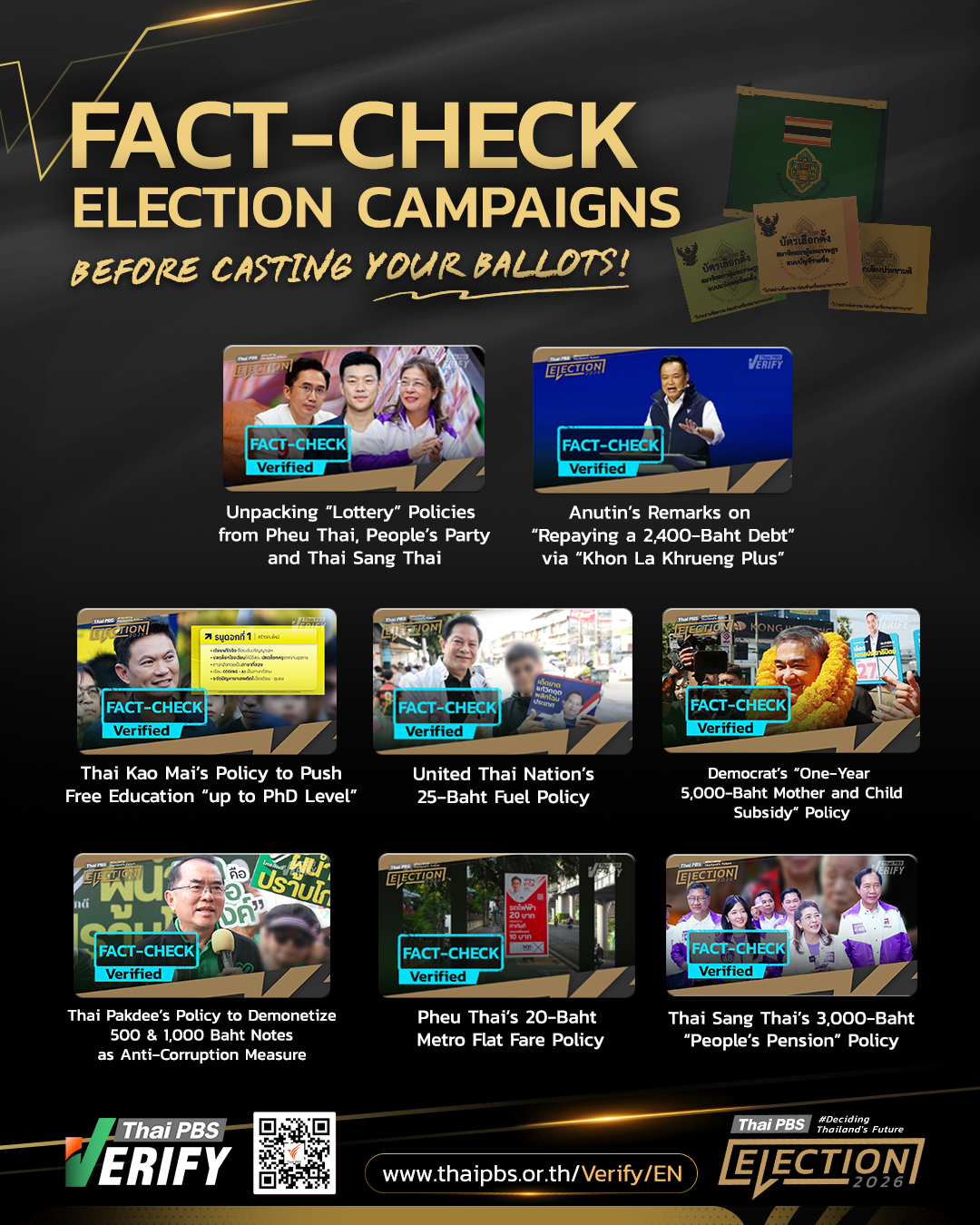

The question Thai PBS Verify is asked most often is why it chooses to use a bright blue label with the words “fact-check” and “verified” instead of stamping content as “true” or “false.”

The answer is simple but not easy to put into practice because political fact-checking cannot use definitive language without creating side effects.

The terms “fake news” or “true news,” when placed in a political context, can immediately be interpreted as correcting the narrative for one side or attacking the other. The complexity of political truth cannot be squeezed into a simple black-and-white frame.

Especially during sensitive election periods, making a definitive judgment can also lead to legal disputes and accusations of media bias. Explaining claims based on evidence, being transparent about the process, and allowing the public to decide for themselves is therefore the more responsible approach.

This approach aligns with international standards set by fact-checking organizations such as the International Fact-Checking Network (IFCN), which prioritizes process over verdicts.

Fact-checking is not meant to make you believe, but to make you think

The mission of Thai PBS Verify is not to make audiences believe something just because they see a label on an image. It encourages audiences to pause, read, verify, and think for themselves. Non-definitive labels force audiences to move beyond snap judgments based on first impressions and return to the reasoning, evidence, and sources behind the information. This is not the weakness of fact-checking, but its very core.

The bright blue color chosen carries no political meaning. It is simply a color that does not compete for attention with the content, because in the end, what truly matters is not the color of the sign, but the quality of the information inside it.

And that is why Thai PBS Verify chooses to walk a careful path, in order to preserve the truth in the most complex spaces of a democratic society.

The election may be over, but the fight against dis/malinformation is far from finished. A strong democracy is not measured solely by the number of ballots in the box, but by the quality of the information in the hands of the people—information that is sufficient for thoughtful consideration, careful enough to guide choices, and honest enough not to distort the future of this society.

If you encounter suspicious images or news reports, you can send the details to the Thai PBS Verify team via Facebook: m.me/ThaiPBSVerify or email: Verify@thaipbsverify