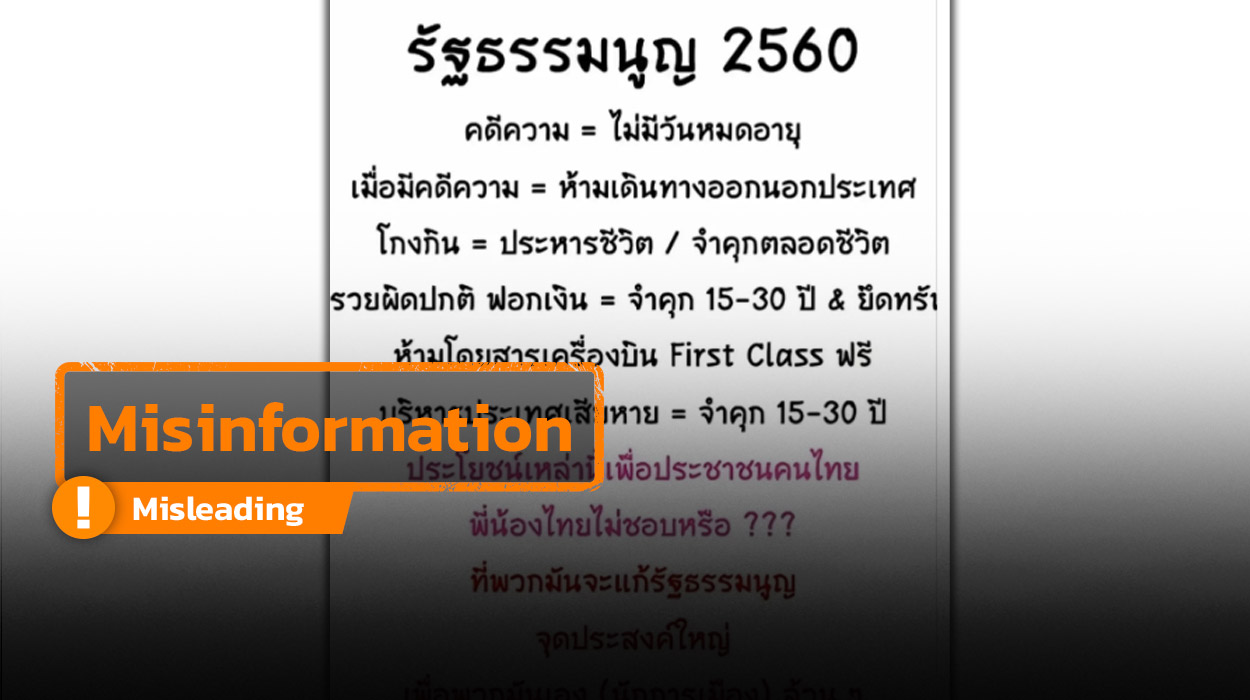

Thai PBS Verify found the source of misinformation on: Facebook

A post was found claiming information regarding the amendment of the 2017 Constitution, stating that if the Constitution were amended, it would cause a loss of benefits to Thai people and that the constitutional amendments were set to create political advantages.

The post’s caption is as follows:

2017 Constitution

Legal cases = No statute of limitations.

When a case is pending: there is a prohibition on traveling out of the country.

Corruption = Death penalty / Life imprisonment.

Unusual wealth and money laundering = 15–30 years imprisonment, asset seizure, and a ban on free First-Class air travel

Administrative malpractice causing national damage = 15–30 years imprisonment.

These benefits are for the Thai people. Do our Thai people not like this? The primary purpose of amending the Constitution is entirely for their own benefit (politicians’).

Chapter 4: Duties of the Thai People

Chapter 5: Duties of the State

Chapter 6: Directive Principles of State Policies

Chapter 7: The National Assembly

- Part 1: General Provisions

- Part 2: The House of Representatives

- Part 3: The Senate

- Part 4: Provisions Applicable to Both Houses

- Part 5: Joint Sittings of the National Assembly

Chapter 8: The Council of Ministers

Chapter 9: Conflict of Interest

Chapter 10: The Courts

- Part 1: General Provisions

- Part 2: Courts of Justice

- Part 3: Administrative Courts

- Part 4: Military Courts

Chapter 11: Constitutional Court

Chapter 12: Independent Organs

- Part 1: General Provisions

- Part 2: Election Commission

- Part 3: Ombudsmen

- Part 4: National Anti-Corruption Commission

- Part 5: State Audit Commission (Sections 238–245)

- Part 6: National Human Rights Commission

Chapter 13: State Attorney Organ

Chapter 14: Local Administration

Chapter 15: Amendment of the Constitution

Chapter 16: National Reform

Transitory Provisions

Regarding the information on the amendment of the 2017 Constitution from the image, is it a fact?

When referencing the content of the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2560 (2017), it is found that there are no provisions specifying the penalties or conditions as claimed in the post, whether it be the requirement that legal cases have no statute of limitations, prohibition on traveling abroad, death penalty for corruption cases, or penalties regarding the ban on first-class air travel.

The content structure of the 2017 Constitution is divided into 16 Chapters and Transitory Provisions, covering general principles, state structure, rights and liberties of the people, duties of the state, and the powers and duties of constitutional organs, including the process of checks and balances. Details regarding offenses, criminal penalties, or specific punishments are stipulated in subordinate laws, such as the Criminal Code or other specific legislation, and are not directly contained within the Constitution itself.

The content of the 2017 Constitution consists of 16 Chapters, including Transitory Provisions, as follows:

Chapter 1: General Provisions

Chapter 2: The King

Chapter 3: Rights and Liberties of the Thai People

Facts regarding the claims about the 2017 Constitution

Regarding the claim that “Legal cases = No statute of limitations,” the fact is that the 2017 Constitution contains no provisions concerning the statute of limitations for such criminal cases. However, the matter of legal proceedings appears in the Organic Act on Anti-Corruption, B.E. 2561 (2018), Section 7, which stipulates that the period during which an accused person or defendant absconds during legal proceedings shall not be counted toward the statute of limitations. Furthermore, if an individual absconds while subject to a final judgment sentence, the provisions regarding the statute of limitations under the Criminal Code shall not apply.

Regarding the claim “When a case is pending = Prohibition on traveling out of the country,” the fact is that the Constitution does not stipulate such a prohibition. The restriction of travel is a judicial power under Section 108 of the Criminal Procedure Code, which allows the Court to impose conditions for provisional release (bail), including prohibition on leaving the Kingdom. Furthermore, the Organic Act on Anti-Corruption, B.E. 2561 (2018), Section 39, stipulates that such provisions shall be applied mutatis mutandis.

Regarding the claim that “Corruption = Death penalty / Life imprisonment,” the fact is that the 2017 Constitution contains no provisions for criminal penalties. Death penalty and life imprisonment for corruption offenses are instead stipulated in the Criminal Code, Sections 148, 149, 201, and 202, which pertain to offenses against official positions and the judicial process. Meanwhile, the Organic Act on Anti-Corruption does not prescribe death penalty, but it does include life imprisonment in certain cases, such as Sections 173 and 174, concerning the unlawful demand or acceptance of assets or benefits.

Regarding the claim that “Unusual wealth and money laundering = 15–30 years’ imprisonment,” the fact is that Sections 234–236 of the 2017 Constitution define powers and duties of the National Anti-Corruption Commission (NACC) in investigating cases of unusual wealth, but they do not prescribe specific penalties. Criminal penalties are instead found in other legislation, such as the Organic Act on Anti-Corruption, Section 167, which stipulates penalties for filing false asset declarations, and the Anti-Money Laundering Act, B.E. 2542 (1999), Section 60, which prescribes imprisonment ranging from 1 to 10 years.

Regarding the claim that “Administrative malpractice causing national damage = 15–30 years’ imprisonment,” the fact is that the Constitution contains no provisions for penalties in such cases. Criminal liability for state officials is instead stipulated in the Criminal Code, Section 157, and the Organic Act on Anti-Corruption, Section 172, which prescribe imprisonment ranging from 1 to 10 years.

Regarding the claim about the “Ban on complimentary First-Class air travel,” the fact is that regulations concerning first-class air travel are not contained within the Constitution. Instead, they are defined under the Royal Decree on Officials’ Travel Expenses (No. 9), B.E. 2560 (2017), Sections 53 and 53/1, which specify the conditions and positions eligible for such entitlements.

From the content of the post claiming these are provisions of the 2017 Constitution, it is found to be distorted information. As the supreme law of the land, the Constitution serves to define the structure of state power, governing principles, and the protection of the people’s rights and liberties; it does not contain direct provisions for criminal penalties as claimed in the post.

If the Constitution is amended, will organic laws and other legislation disappear?

Dr. Stithorn Thananithichot, lecturer at the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University, explains that enacting a new Constitution to replace the previous one does not automatically terminate the enforcement of various laws. This is because subordinate and general laws remain in effect unless there are specific provisions in the new Constitution that mandate their repeal or amendment.

“According to the fundamental principles of constitutional transition, when a new Constitution is enacted, the old one ends. But all subordinate laws (including Acts and Organic Acts) remain in force, except for those laws that are inconsistent with or contrary to the new Constitution.”

Dr. Stithorn Thananithichot, lecturer at the Faculty of Political Science, Chulalongkorn University. (Image by The Active)

“According to the rule of law, if all laws were to terminate simultaneously with a new Constitution, legal chaos would ensue. State agencies would be unable to perform their duties, and the rights and obligations of the people would become uncertain. Therefore, modern constitutional systems adhere to the principle that changing the Constitution is not equivalent to resetting the entire legal system.”

Furthermore, Dr. Stithorn stated that the actual practice applied in all previous Thai Constitutions follows the same principle: “All laws in force before the date of the enforcement of this Constitution shall remain in force insofar as they are not inconsistent with or contrary to this Constitution.” Such clauses typically appear in the “Transitory Provisions” found in almost every Constitution.

“Regarding the practice concerning Organic Acts, the same applies. Although Organic Acts are, in principle, closely linked to the Constitution, they do not terminate immediately. The established practice is for them to remain in force “temporarily” until new Organic Acts are enacted to align with the new Constitution. So, it is common to see provisions in a succeeding Constitution stating: ‘The existing Organic Acts shall continue to apply for the time being,

insofar as they are not inconsistent with or contrary to the new Constitution.’”

Under Section 130 of the 2017 Constitution, there are a total of 10 Organic Acts, as follows:

- Organic Act on Election of Members of the House of Representatives

- Organic Act on Installation of Senators

- Organic Act on Election Commission

- Organic Act on Political Parties

- Organic Act on Ombudsmen

- Organic Act on Prevention and Suppression of Corruption

- Organic Act on State Audit

- Organic Act on Procedures of the Constitutional Court

- Organic Act on Criminal Procedure for Persons Holding Political Positions

- Organic Act on Human Rights Commission

The main point is that other laws will terminate only in the following cases.

- The new Constitution explicitly stipulates their replacement.

- The content of the law is inconsistent with or contrary to the new Constitution.

- New legislation has been enacted to replace them.

Academic perspectives on “election and referendum guidance movements” set to obstruct a new constitution

Associate Professor Olarn Thinbangtieo, Faculty of Political Science and Law, Burapha University, analyzes that in the current political context, Information Operations (IO) are being utilized to manipulate trends and create a “new set of truths” that are not based on facts. These operations aim to influence public decision-making in both elections and referendums. It is to persuade the public to vote for a specific political party, and shape public perception into feeling that a new draft constitution should not be accepted.

This process has emerged because there is a high public demand for a new constitution to be drafted, which would significantly impact the established old power networks.

Associate Professor Olarn Thinbangtieo, Faculty of Political Science and Law, Burapha University

Furthermore, it is observed that the 2017 Constitution serves as an “Architecture of Power” specifically designed to protect and preserve the power and interests of the elite. A prominent characteristic of this structure is the utilization of mechanisms through independent organs and various tools to easily remove opponents or conflicting parties from power. Consequently, there are ongoing efforts to obstruct any easy amendments to the Constitution to maintain these instruments for safeguarding such interests.

What is the truth?

According to the verification, it was found that the Constitution of the Kingdom of Thailand, B.E. 2560 (2017), does not contain provisions specifying criminal penalties or other sanctions directly as claimed, whether regarding cases without a statute of limitations, travel prohibitions, death penalty, 15–to-30-year imprisonment and entitlement to first-class air travel. All of these fall under the authority and penalties prescribed in subordinate or specific laws, such as the Criminal Code and anti-corruption legislation; they are not contained within the Constitution itself. At the same time, amending or drafting a new Constitution does not automatically terminate the enforcement of organic laws or other legislation, except in cases where such laws are inconsistent with or contrary to the new Constitution, or if they are explicitly repealed in its provisions or transitory provisions.

Legal Source: Tassanai Chaikhuang, Attorney-at-Law, KSS Law Office